-

Cosmedocs| Non Surgical

-

COSMESURG| Surgical

-

HARLEY STREET| Skin Care

FORMULATIONS -

| Skin Bar Clinic

GLOW & GO

GLOW & GO

Age’s Impact on The Aesthetic Units of the Face

What morphological changes occurwith ageing?

During youthful years, the face manifests as one single dynamic unit with smooth facial contours and little shadowing between different facial features. However, as we age the face gradually morphs into distinct separate facial units. This process may result from changes in the thickness of skin, subcutaneous tissue composition, facial skeleton contours and the location of facial ligaments[1][2]. The combination of superficial visual changes to the skin and the deeper compartmentalisation of facial features, leads to the overall appearance of an aged face.

The ageing of a face is a gradual yet constant process that involves evolving of the bony facial structure and overlying soft tissues. This natural and uncontrollable ageing process is called internal or intrinsic ageing, whereby soft tissue maturation, the effects of gravity and the constant activity of facial muscles (combined with their eventual reduction in strength), changes the appearance of the face. Skeletally, bone movement, growth, deformations and stomatognathic system changes all affect facial structure over time[3]

Visual differences as the soft tissue matures, include a change in the colour and texture of the skin and the formation of lines and wrinkles.

This intrinsic ageing process is affected by hereditary factors to a degree and is largely beyond our control. In comparison, extrinsic ageing is the result of our lifestyles. Factors such as smoking, sun exposure and dietary choices all influence how we age.

Changes in the skin:

The most visually prominent age-related changes in the skin result form chronic exposure to the sun; changes in colour (hyperpigmentation), tone (age spots) and texture (lines and wrinkles) are a result of photo-ageing.

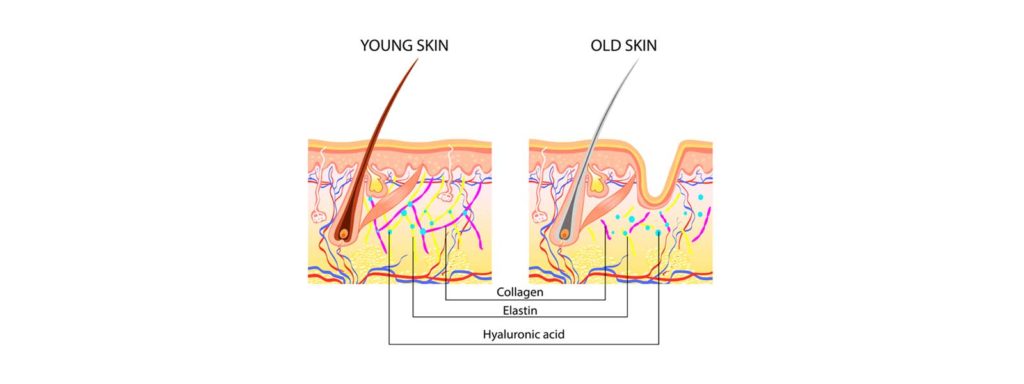

Anatomically as skin ages:

- Collagen production slows down (collagen contributes to the firmness of skin)

- Production of elastin decreases (elastin contributes to elasticity of skin)

- Fat cells start to diminish (resulting in sagging skin)

- The skin’s ability to retain moisture decreases

- Frown lines appear due to repetitive contraction of small muscles

- The shedding of superficial dead skin cells slows down (leading to a dull appearance)

- The turnover of new skin cells reduces

Microscopically, it is possible to see cellular age-related changes. Epidermal thinning, collagen loss and dermal-epidermal junction flattening can be seen. The skin loses its natural elasticity and increased transepidermal water loss occurs.

Dry skin is a consequence of both reduced water-binding capacity and decreased activity of sebaceous gland[3]. This loss of skin elasticity and volume, along with repeated activity of muscles, contributes to the formation of rhytides[4] over the habitual muscle contraction regions such as the orbicularis oculi and oris, risorius, frontalis, and corrugators, etc.

In intrinsic ageing, the papillary organisation of subcutaneous vasculature is lost and the interface of epidermis and dermis flattens resulting in atrophy of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The organisation of elastin and collagen is lost with a reduction in their relative amount, and they exhibit histologic signs of degeneration[5]. The production of TypesI and III collagen by fibroblasts is decreased[6]. Fibroblasts, particularly those located within the papillary dermis, exhibit a selective decline in function and number as compared to those located in the reticular dermis[7].

Smoking, photodamage and the effects of other environmental factors contribute to the increase in intracellular reactive oxidative species resulting in multiple skin changes that lead to characteristics that are consistent with skin ageing[8][9]. This is accompanied by age or dark spots and hyperpigmentation on skin’s surface, caused by increased production of melanin due to excessive sun exposure.

Changes in Volume

A youthful face is characterised by appropriately filled facial fat compartments in their anatomically correct places. Due to progressive ageing, the subcutaneous fullness of the forehead region, brows, temple and upper eyelid region is lost. This makes the bony structure of the skull, supra-orbital rims, brow muscles and the temporal blood vessels more pronounced. Fat redistribution, accumulation and atrophy cause loss of facial volume[10]11].

- Some facial areas lose fat such as the forehead and cheeks

- Other facial areas gain fat such as the mouth and jaw

- These changes in fat pads cause contour deficiencies[12].

The zygomatic-cutaneous, orbitomalar, and mandibular retaining facial ligaments attenuate, which gives a drooping appearance to the soft facial tissues. These act as a hammock for the atrophied compartments of facial fat and soft tissues, which contribute to the appearance of tear trough, malar bags and jowling[13][14][15][16]. The deflation, as well as the decrease in the normal anatomical subcutaneous fat compartments of the face, contributes to an increase in skin laxity and distinct folds that appear around the nasolabial region, periorbital region, and jowl.[17][18][19]

The illustrations above demonstrate that as ageing occurs, the fat compartments become increasingly spaced apart, visually appearing as separate entities rather than a smooth nearly continuous layer[20]

Changes in shape

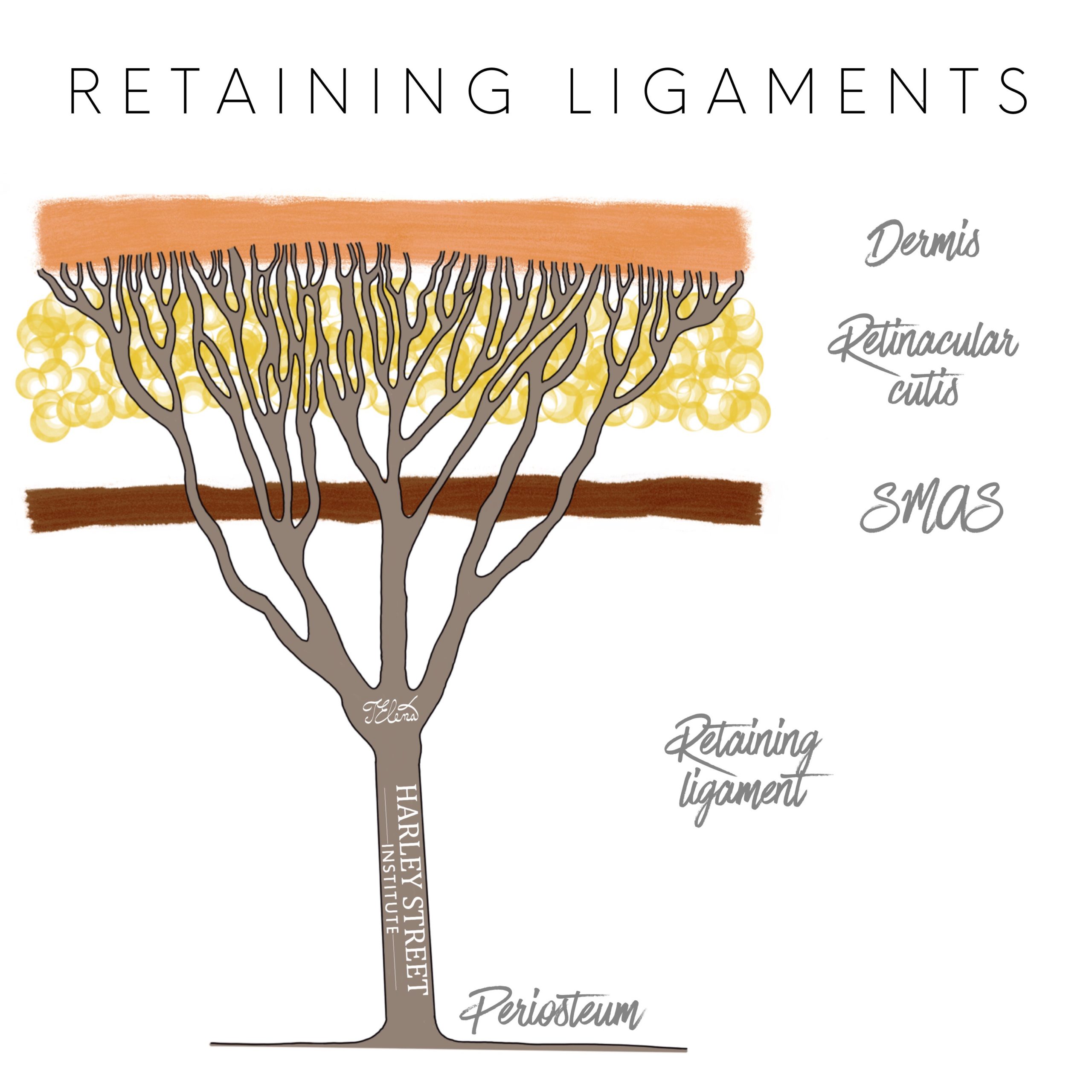

The shape of the face is determined by the underlying anatomy of the muscles and their supporting ligaments. Ligaments are the fundamental supporting structures of the face. The relationship that exists between ligaments, the SMAS, lower eyelid and lateral canthus has been extensively described in various studies. The orbicularis oculi muscle gets support through adhesion to the temporalis, and zygomaticomalar ligaments suspend the cheeks. The infraorbital area has superficial and the deep fat pads that are suspended by a ligament which originates at the arcus marginalis, called the “orbicularis retaining ligament” or the “orbitomalar ligament”[21].

Mendelson has provided extensive details about ligaments, septae, brow adhesion zones, the periocular region, and midface[22][23][24]. He suggested that the laxity of ligaments might be a primary reason for facial ageing. Mendelson hypothesised that the ligaments stabilise the youthful face, but constant activity of facial muscles combined with intrinsic ageing changes, cause ligamentous support weakness[25]. This progressive lack of structural support for the face, combined with the pull of gravity leads to ptosis of the soft facial tissues and the “drooping” aged appearance.

Mendelson has provided extensive details about ligaments, septae, brow adhesion zones, the periocular region, and midface[22][23][24]. He suggested that the laxity of ligaments might be a primary reason for facial ageing. Mendelson hypothesised that the ligaments stabilise the youthful face, but constant activity of facial muscles combined with intrinsic ageing changes, cause ligamentous support weakness[25]. This progressive lack of structural support for the face, combined with the pull of gravity leads to ptosis of the soft facial tissues and the “drooping” aged appearance.

Bottom Line

The combination of visibly apparent skin changes as well as underlying structural disparities, involving bone, muscles, fat and ligaments is responsible for the ageing appearance of the face.

1- Coleman SR, Grover R. The anatomy of the aging face: volume loss and changes in 3-dimensional topography. AesthetSurg J. 2006;26(1S):S4-S9.

Rzany B, Carruthers A, Carruthers J, et al. Validated composite assessment scales for the global face. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(special issue 2):294-308

González-UlloaM. Regional aesthetic units of the face.PlastReconstr Surg. 1987;79(3):489-490.

2 – Tan SL, et al. The Aesthetic Unit Principle of Facial Aging.JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2015 Jan-Feb.

3 – Zimbler, M., M. Kokoska, and J. Thomas, ‘Anatomy and pathophysiology of facial aging’. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America, 2001. 9(2): p. 179-87, vii.

4 – Desai, S., M. Upadhyay, and R. Nanda, ‘Dynamic smile analysis: changes with age’. American Journal of Orthodontics and DentofacialOrthopedics, 2009. 136(3): p. 310. e1-310. e10.

5 – Uitto J. The role of elastin and collagen in cutaneous aging: intrinsic aging versus photoexposure. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7(2 Suppl):s12–6

6 – Varani J, Dame MK, Rittie L, et al. Decreased collagen production in chronologically aged skin: roles of age-dependent alteration in fi broblast function and defective mechanical stimulation. Am J Pathol. 2006;168(6):1861–

7 – Mine S, Fortunel NO, Pageon H, Asselineau D. Aging alters functionally human dermal papillary fibroblasts but not reticular fibroblasts: a new view of skin morphogenesis and aging. PLoS One. 2008;3(12):e4066.

8 – Hinderer UT. Correction of weakness of the lower eyelid and lateral canthus. Personal techniques. ClinPlast Surg. 1993;20:331–349.

9 – Schlessinger J, Kenkel J, Werschler P. Further enhancement of facial appearance with a hydroquinone skin care system plus tretinoin in patients previously treated with botulinum toxin Type A. AesthetSurg J. 2011;31:529–539.

10 – Zimbler MS, Kokoska MS, Thomas JR. Anatomy and pathophysiology of facial aging. Facial PlastSurgClin North Am. 2001;9:179-187.

Donofrio LM. Fat distribution: a morphologic study of the aging face. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:1107-1112.

11 – Vleggaar D, Fitzgerald R. Dermatological implications of skeletal aging: a focus on supraperiostealvolumization for perioral rejuvenation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:209-220.

12 – Vleggaar D, Fitzgerald R. Dermatological implications of skeletal aging: a focus on supraperiostealvolumization for perioral rejuvenation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:209-220.

Donofrio LM. Fat distribution: a morphologic study of the aging face. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:1107-1112.

13 – Stuzin JM, Baker TJ, Gordon HL. The relationship of the superficial and deep facial fascias: relevance to rhytidectomy and aging. PlastReconstr Surg. 1992;89:441

14 – Reece EM, Pessa JE, Rohrich RJ. The mandibular septum: anatomical observations of the jowls in aging-implications for facial rejuvenation. PlastReconstr Surg. 2008;121:1414–1420.

15 – Furnas DW. The retaining ligaments of the cheek.PlastReconstr Surg. 1989;83:11–16.

16 – Barton FE.,Jr The SMAS and the nasolabial fold. PlastReconstr Surg. 1992;89:1054.

17 – Gonzalez-Ulloa M, Flores ES. Senility of the face—basic study to understand its causes and effects. PlastReconstr Surg. 1965;36:239–246.

18 – Rohrich RJ. Ethical approval of clinical studies, informed consent, and the Declaration of Helsinki: what you need to know. PlastReconstr Surg. 2007;119:2307–2309.

19 – Rohrich RJ, Pessa JE, Ristow B. The youthful cheek and the deep medial fat compartment.PlastReconstr Surg. 2008:2107–2112.

20 – Vieggaar D, Fitzgerald R. Dermatological implications of skeletal aging: a focus on supraperiostealvolumization for perioral rejuvenation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:209-220.

21 – Muzaffar AR, Mendelson BC, Adams Jr WP. Surgical anatomy of the ligamentous attachments of the lower lid and lateral canthus.PlastReconstr Surg. 2002;110(3):873–84.

Ghavami A, Pessa JE, Janis J, et al. The orbicularis retaining ligament of the medial orbit: closing the circle. PlastReconstr Surg. 2008;121(3):994–1001.

Kikkawa DO, Lemke BN, Dortzbach RK. Relations of the superficialmusculoaponeurotic system to the orbit and characterization of the orbitomalar ligament.OphthalPlastReconstr Surg. 1996;12(2):77–88.

Mendelson BC, Jacobson SR. Surgical anatomy of the midcheek: facial layers, spaces, and the midcheek segments. ClinPlast Surg. 2008;35(3):395–404.

22 – Mendelson BC, Muzaffar AR, Adams Jr WP. Surgical anatomy of the midcheek and malar mounds.PlastReconstr Surg. 2002;110(3):885–96.

23 – Mendelson BC. Surgery of the superficialmusculoaponeurotic system: principles of release, vectors, and fixation. PlastReconstr Surg. 2001;107(6):1545–52.

24 – Mendelson BC. Surgery of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system: principles of release, vectors, and fixation. PlastReconstr Surg. 2001;107(6):1545–52.

Philip Gray

Related Posts

We use cookies to give you the most relevant experience, Cookie Policy.

Botox & Dermal Filler Course

*excluding VAT

See What Our Fellows Have Been Up to Recently

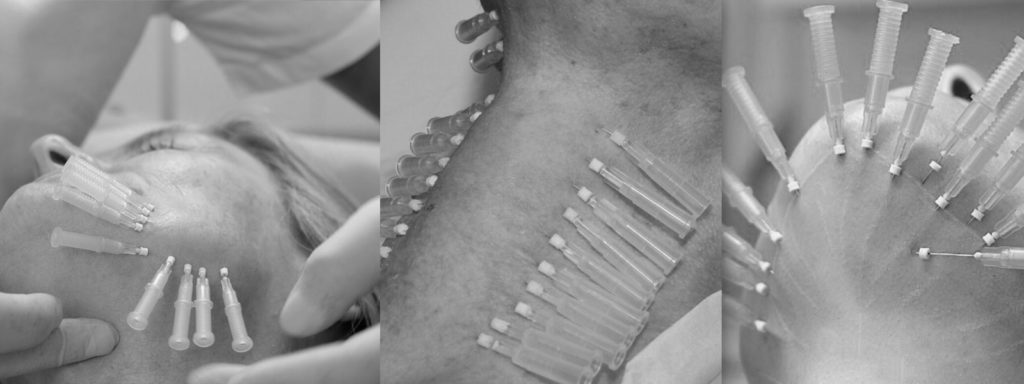

Understanding depth, volume, and pressure can enhance a practitioner’s skill set, enabling them to provide more valuable services to their clients using their existing tools. #aestheticmedicine #dermalfillertraining #wrinklefree

Mastering hand stability isn’t magic, it’s a mix of experience & targeted learning 🎯 Our students get ahead with specialized techniques, paving the way for precise injections! 💉#SkillDevelopment #FutureHealthPros

.

.

.

.

.

#dermalfillertraining #aestheticmedicine #botoxtraining

Virtually any area can be reached using a cannula #fillertraining #aestheticmedicine #hsifellowprogram

“Unlock Your Aesthetic Potential with Harley Street Institute’s Fellowship! 🌟 Elevate your skills in aesthetic medicine through our intensive hands-on training in Botox and Dermal Fillers. Get ready to sculpt beauty, one injection at a time! 💉✨ Join us for a transformative learning journey that takes you beyond the classroom and into real-world expertise. Are you ready to master the art of enhancing natural beauty? 💫 #HarleyStreetFellowship #AestheticMedicineMastery #SculptingBeauty”

Link in bio

"Unlocking the Secrets of Masseter Botox: Empowering smiles, one injection at a time! 💉💪 Join me on an exciting journey as we delve into the world of Masseter Botox. Learn the art and science behind this transformative procedure, and discover how it can redefine facial aesthetics. Don`t miss out on this opportunity to enhance your skills and expand your practice. Let`s reshape faces and build confidence together!

Link in bio.

#MasseterBotoxCourse #FacialAesthetics #TransformativeProcedures #SmileEnhancement #ContinuingEducation

#aestheticmedicine

💭Have You Ever thought :

👉🏼What lies beneath the orbicularis oculi ?

👉🏼Why do I need to have the correct depth ?

👉🏼How to avoid an asymmetric smile, periorbital edema or a shelf like look at the lid/cheek junction ?

⚠️We all know that when treating crows feet, we are administering botox into the orbicularis oculi, and that there are complications but which and how?

‼️Too inferior or deep🟰 an asymmetric smile

(you’ve hit the zygomaticus minor muscle and major if you’re really too inferior!)

‼️Too medially 🟰 periorbital edema

(and you’re the periorbital region )

Located just underneath the skin, the orbicularis oculi has multiple origin and insertion points. A paired muscle, that overlies the periorbital region in a circular manner.

⚠️The wrong location, the wrong depth can result you injecting botox into a completely different muscle.

Welcome to the under eye region, an area of the face that can often show signs of aging such as wrinkles, hollows, and dark circles. Today, I want to share with you how fillers can be used to address these concerns by injecting them into different layers of the skin.

Using a needle, we can inject fillers into the dermis layer of the skin to improve the appearance of fine lines and wrinkles. This can help to smooth out the texture of the skin and create a more youthful and refreshed look. However, it’s important to note that injecting fillers into this layer requires specialized training and experience to ensure safe and effective results.

In addition to the dermis layer, fillers can also be injected into the bone to help address deeper hollows and shadows under the eyes. This technique requires a higher level of expertise as it involves precise placement of the filler to achieve the desired outcome.

Lastly, fillers can be injected into the fat compartment of the under eye region using a cannula. This method can help to add volume and smooth out any irregularities in the fat pads under the eyes. Again, specialized training and experience are crucial for safe and effective results.

Overall, the use of fillers in the under eye region can provide a non-surgical solution to address signs of aging and enhance the appearance of the face. However, it’s important to seek out a qualified and experienced provider who has received proper training in the use of fillers in this delicate area.

If you’re interested in learning more about how fillers can benefit you, please don’t hesitate to reach out and schedule a consultation. Let’s work together to help you achieve your aesthetic goals!

#cosmedocs #harleystreetinstitute

.

.

.

.

#lifestyleblogger

#selfcarematters #aestheticmedicine

#beautytips

#skincarecommunity

#antiagingtips

#makeuptutorials

#selfcarelove

#aestheticbeauty

#lifestyleinspo #lifestyleblogger

#selfcarematters #dermalfillertraining

#beautytips

#skincarecommunity

#antiagingtips

#makeuptutorials

#selfcarelove #dermalfillers

#aestheticbeauty

#lifestyleinspo

#antiagingsecrets

#harleystreet #drahmedhaq #oxforduniversity

#harleystreetinstitute

The mentalis muscle is a facial muscle located in the chin area. It originates from the mandible and extends downward to the skin of the chin. The primary function of the mentalis muscle is to control the movement and position of the lower lip and the skin of the chin. It plays an important role in activities such as speaking, smiling, and pouting.

In addition to its role in facial expression, the mentalis muscle also helps to maintain the position of the lower front teeth and the shape of the lower lip. Dysfunction or hyperactivity of the mentalis muscle can lead to the development of chin wrinkles, which are vertical lines that appear on the skin of the chin. Understanding the anatomy and function of the mentalis muscle is important for healthcare providers when performing aesthetic procedures in the chin area.

Online Course With Video Demo

www.harleystreetinstitute.com

#botoxtraining #mentalistreatment

#Repost @dranabilamzavala with many thanks 🙏 and best wishes for the future.

Esta semana tuve la oportunidad de estar en Londres en una de las mejores clínicas con los mejores equipos de Medicina Estética en el mundo, perfeccionado técnicas de Rinomodelación con el Dr.Ahmed Haq.

——

@drahmedhaq You are simply incredible, thanks for the hands on and all the new techniques you shared. @drahmedhaq @harleystreetinstitute @cosmedocs

.

.

.

#aestheticmedicine #dermalfillertraining #nosejob #medicaltraining #plab #harleystreet #10harleystreet #aesthetics

Huge Congratulations to Mariana, on completing her foundation course in Aesthetics Medicine with us here at Harley Street Institute. 🥇✨

This combined course covers the necessities required for daily clinic practise, whether starting out or refreshing skills. Our small group training (4:1) provide unparalleled mentorship at any of our training days.

#cosmetictraining #aesthetics #hsi #cosmetics #cosmedocs #harleystreetcourses #foundationcourse #london

Only courses with true mentorship. #botoxtraining #dermalfillertraining #aestheticmedicine #hsifellowprogram #harleystreetfellowship

Huge congratulations to @onemedicalclinic for completing her Fellowship in aesthetic Medicine with us at Harley Street Institute 💫💫✨ We are so proud of having you 🥰

#Repost

Dr Crystal:”When I completed medical school 13 years ago, one of my cherished mentors gave me advice that has stayed with me for life - “never stop learning; it makes the difference between being good and being great."

From my years of Ophthalmic-surgical training to becoming a student of Public Health to my experience as a legislator in Parliament to operating my own

Medical and Aesthetic Medical practice, the lessons learned have been varied and valuable. 🤓

On this occasion my commitment to lifelong learning led me to Harley Street, London. I didn’t just want to be a good injector, I needed to be a great one so I needed to go where the great injectors were. 💉

Every day for the last two months I was immersed in one-on-one intensive training with the aim of mastering my injectable skills and thanks to the incredible team of doctors and trainers at @cosmedocs

@harleystreetinstitute l am proud to say Mission Accomplished! “

Huge Congratulations to Dale Rae for completing the Certificate in Aesthetic Medicine training program. 💫💫

💉The 3-day Aesthetic Medicine Certificate is tailored towards new practitioners who are ready to kick-start their career in Aesthetic Medicine. It aims to provide an in-depth understanding of the Layers of the Skin and Biological Ageing Process. The package also includes our most popular Foundation Botulinum Toxin and Dermal Fillers course, including an introduction to using cannula.

💉It is an Intense 3-day course incorporating essentials basic and advanced botox and dermal filler procedures combined with popular skin treatments perfect for the beginner all-rounded aesthetic practitioner.

You will be provided direct mentorship by our various cosmetic practitioners who are experts in performing their respective aesthetic treatments.

💉Small group training under the direct supervision of our experienced aesthetic trainers. Master procedures to an advanced level. Learn theory, consultation methods and manage client expectations as well as complications.

🙌 DM for more details. #aesthetic #dermalfillers #detmalfillertraining

Aesthetic medicine is an art. It`s not enough to know facial anatomy or to be a good injector. The best aesthetic doctor has an artistic eye. Sometimes this is a skill that can be developed over years. Being able to assess a fa ce within seconds of walking into a room. Knowing exactly how injectables can be used for subtle and natural results.

The end result should not be obvious to an untrained eye.

It`s such a shame to see overfilled faces exaggerating proportions. When really, the main aims are to restore volume lost or correct natural imbalances.

#aestheticmedicine #dermalfillers #beauty

Repost @cosmedocs

Huge Congratulations to @erikatydermatology for completing her Fellowship in Aesthetic Medicine with us at the Harley Street Institute 💫💫💫

Our Aesthetic Fellowship is the pinnacle of training for those seriously interested in escalating their careers.

.

Our fellows are taken on board within clinic over 3 months with weekend workshops, 1-1 mentoring, treatment log book and clinical assistance.

.

Following on from this they have the opportunity to have Independent Fellow Clinics to improve their confidence with patient consultation and individual treatment planning.

.

We believe that this is the future of aesthetic traning to ensure that practitioners have captured all the essential skills for successful careers.

.

We have been extremely proud of our old fellows, many who have moved on to now work with some of the most prestigious clinics in London.

.

Next enrolment periods: TBC

.

To find out more information or to apply, please email your CV to [email protected]

.

#thefellowship #harleystreetinstitute #doctorsanddentists

KISS

As the years some procedures get unnecessarily more complicated without much added benefits. Risks / complications have increased: more inexperienced practitioners , inadequate techniques, increasing consumer demand for bolder augmentation.

#keepitsimplestupid

Note: if you did not get the email, please check spam/junk folder